By Ron Sutton, EAA 29083

On July 20, 1967, when the Stephens Akro was ready for its first flight, the cockpit was filled by Flavio Madariaga of Flabob Airport, Riverside, California. Flavio said, “I’ll take it out and make a couple of taxi tests and see how she handles; if everything is okay, I will take her up.” He slowly taxied the Akro down to the runway for her maiden flight. After run-up procedures and control check, Flavio proceeded to the takeoff spot, lined up on the runway, and cracked the throttle one-quarter; next thing he knew he was 15 feet in the air. He held the stick steady and throttled back, the Akro settled back in as light as a feather.

Flavio taxied back around with the cockpit still open and said, “Might as well close the canopy and go!” (And go it did!) He was off the ground and aloft for 12 minutes, putting the Akro through snaps, slow rolls, loops, and inverted flight. After landing he reported a perfect flight.

After two more such test hops, to confirm the Akro hadn’t any unexpected vices, the late Margaret Ritchie, 1966 National Women’s Aerobatic Champion, took her new airplane up to get acquainted. “It was love at first flight,” her husband reported. Margaret exclaimed, “I hadn’t flown anything that climbed on takeoff like the Akro does. It was a real thrill to look back and see the ground disappearing. It looked like I was standing still and the ground was going backward.”

I was very fortunate in having an opportunity to see the actual construction of the Stephens Akro. My first encounter with the Akro was the wing. It made an impressive sight — 24-foot, 4-inch tapered full cantilever wing, with the bottom skin in place, leaving the ribs and spars open. The ribs were made of birch veneer, spruce cap strips, and birch gussets on a laminated, tapered spar.

To me, this 23012 Airfoil looked to be a lot of work, but Clayton Stephens assure me it wasn’t as difficult as it might seem. Next, the fuselage started to take shape around a 4130 chrome moly airframe. The basic airframe was taken from the 190-cubic-inch racer, Miss San Bernardino, and scaled up one-third with a side view drawing by Ed Allenbaugh. Ed also did the wing drawings, using the same airfoil as Margaret’s Taylorcraft had. Ed passed away shortly after completing these preliminary drawings, and the remaining engineering of the aircraft was done by Clayton during construction.

Each day, I would look in on Clayton as he would slowly and methodically build up the different assemblies throughout the whole aircraft. The simplicity of construction was amazing. The ailerons are torque tubes with wood ribs, aluminum leading edge, and covered with Dacron to finish off the smooth airfoil. All of the fittings are hidden to give an uninterrupted airflow over the wing and control surfaces. The tail feathers are all 4130 tubing with flying wires for added strength. All the controls are push-pull operated for positive response. Thin-gauge aluminum wrapped around plywood and aluminum stringers formed the turtledeck and also enclosed a small luggage compartment. A sliding bubble canopy moves on a ball-bearing wheel track that looks as professional as any manufactured on the market today.

The cockpit is clean cut, military style, to give as much room as possible. A big window was put in the floor to aid Margaret through her aerobatic performances. A 32-gallon aluminum fuel tank is neatly tucked away between the instrument panel and the firewall.

Clayton has been in on the complete construction of three nationally famous aerobatic planes, including Margaret’s clipped wing Taylorcraft, which won the 1966 National Women’s Aerobatic Championship and thrilled crowds all over the USA. Clayton also did the modifications to Art Scholl’s de Havilland Chipmunk that placed in the National Men’s Aerobatic Championship in 1966; it also competed in the 1966 Olympics in Russia and placed third in the National Men’s Aerobatic Championship at Reno in 1967. Last, but not least, is the Stephens Akro, which made its debut in Reno. Margaret flew it with just two months’ practice to a well-deserved second place in the National Women’s Aerobatic Championship.

With this past experience and knowledge of what an aircraft can be put through (in the case of Art Scholl’s Chipmunk), and the beauty and grace of precision aerobatics (as with Margaret’s clipped wing Taylorcraft), Clayton built these long-sought-after traits into the Akro. Simplicity and strength go hand-in-hand with the Akro. This is strongly emphasized in the configuration of the landing gear. The gear legs are one-piece aluminum, bolt-on type, and with the wheels, tires, and brakes, the complete gear installation weighs only 42 pounds. I can honestly say that this landing gear is an amateur aircraft builder’s dream come true (as I am building up a Wittman Tailwind).

Forward of the padded firewall hangs 180 horses on a stock Lycoming engine ring mount. To streamline the engine to the rest of the aircraft, a cowling was made up of a symmetrical nose bowl and aluminum sheet stock with fiberglass blisters for the cylinders.

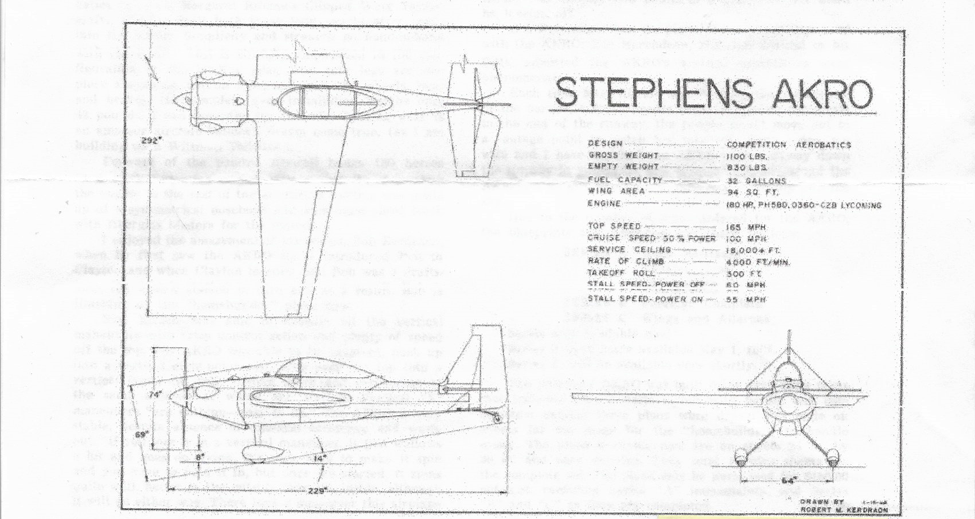

I enjoyed the amazement of my friend Bob Kerdraon when he first saw the Akro fly. I introduced Bob to Clayton, and when Clayton learned that Bob was a draftsman, the wheels started to turn. As a result, Bob is finishing up the “homebuilder” plans now.

Margaret was able to execute all the vertical maneuvers with crisp control action and plenty of speed off the top. The Akro was able to fly inverted, push up into a vertical four-point roll, coming down and recovering at the same altitude at which she started. Vertical “S” maneuvers are easy. The Akro is very stable, despite absence of dihedral incidence and washout. “If you lose it in a vertical maneuver, it just wallows a bit and goes on flying. It’s very hard to make it spin and you have to hold it in, but once it’s started, it spins quite well, better to the outside than the inside, although it will go either way. There isn’t a maneuver this airplane can’t do, but there are some I can’t do yet,” said Margaret.

In the few years Margaret performed competitive aerobatics in the Taylorcraft, she went all the way to the top in national competition. When she was detailing her requirements for the Akro, she specified one more addition to those already named: “I want an airplane that will outperform the Yak.” Little did she know then, that she would be chosen for the USA Olympic Team to compete in international competition.

While at Reno, Dean Englehart, who flies the Disenchanted Champ, flew the Akro. Dean reported, “I flew the Akro to 8,000 feet, and from that altitude noted a rate of climb better than 2,500 feet per minute, so, from an entry speed of 190 miles per hour, I pulled up into a vertical four-point roll, then a loop, and finished off with another roll. It snaps right now.”

At Reno, one of George Ritchie’s friends, John Paul Jones of the famed Pylon Racer Shoestring, flew it. When he landed all he could say was, “Wow! What a plane.”

Art Scholl also flew the Akro. He flew the plane through flutter tests without any trace of flutter. During his testing, he pulled up into a vertical eight-point roll, found the aircraft to have more to give. He said the Akro had another two points left when he leveled off.

Bob Herendeen flew the plane. He, too, was impressed with the Akro. Bob, although faithful to his Pitts Special, admitted the Akro’s vertical capabilities were phenomenal.

Each time Margaret would move the Akro out of the hangar, a crowd would form, and when she’d taxi to the end of the runway, the people would move out to a vantage point to watch her take off. Many times, my wife and I have watched the Akro move halfway down the runway in a typical “Margaret” takeoff: stand the Akro on its tail, and almost disappear vertically into the sky.

Series A — Basic Airframe, Landing Gear, Tail Section: available now

Series B — Fuselage Complete: made available May 1, 1968

Series C — Wings and Ailerons: will be available very shortly

The prototype Akro was built using very basic plans that included only a basic layout with hardly any construction details; these plans were drawn full scale on sheets far too large for the “homebuilder” to handle easily. The plans available now are on sheets 24 inches by 36 inches and very detailed. They total 10-plus sheets for the complete set. The plans may be purchased for $150.00 outright, receiving Series A immediately, and Series B and C as they are completed.

Original article appeared in the July 1968 issue of EAA Sport Aviation.